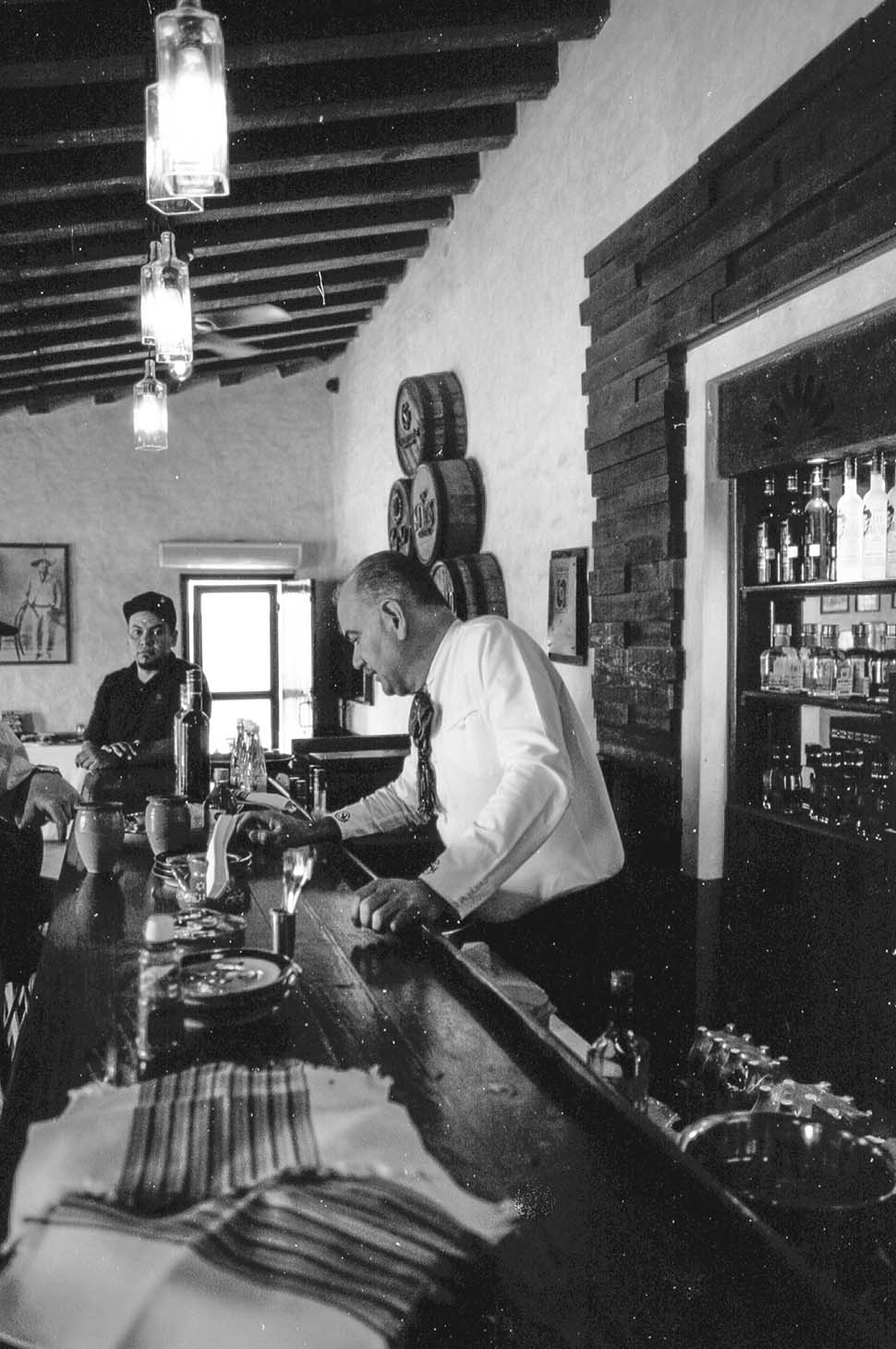

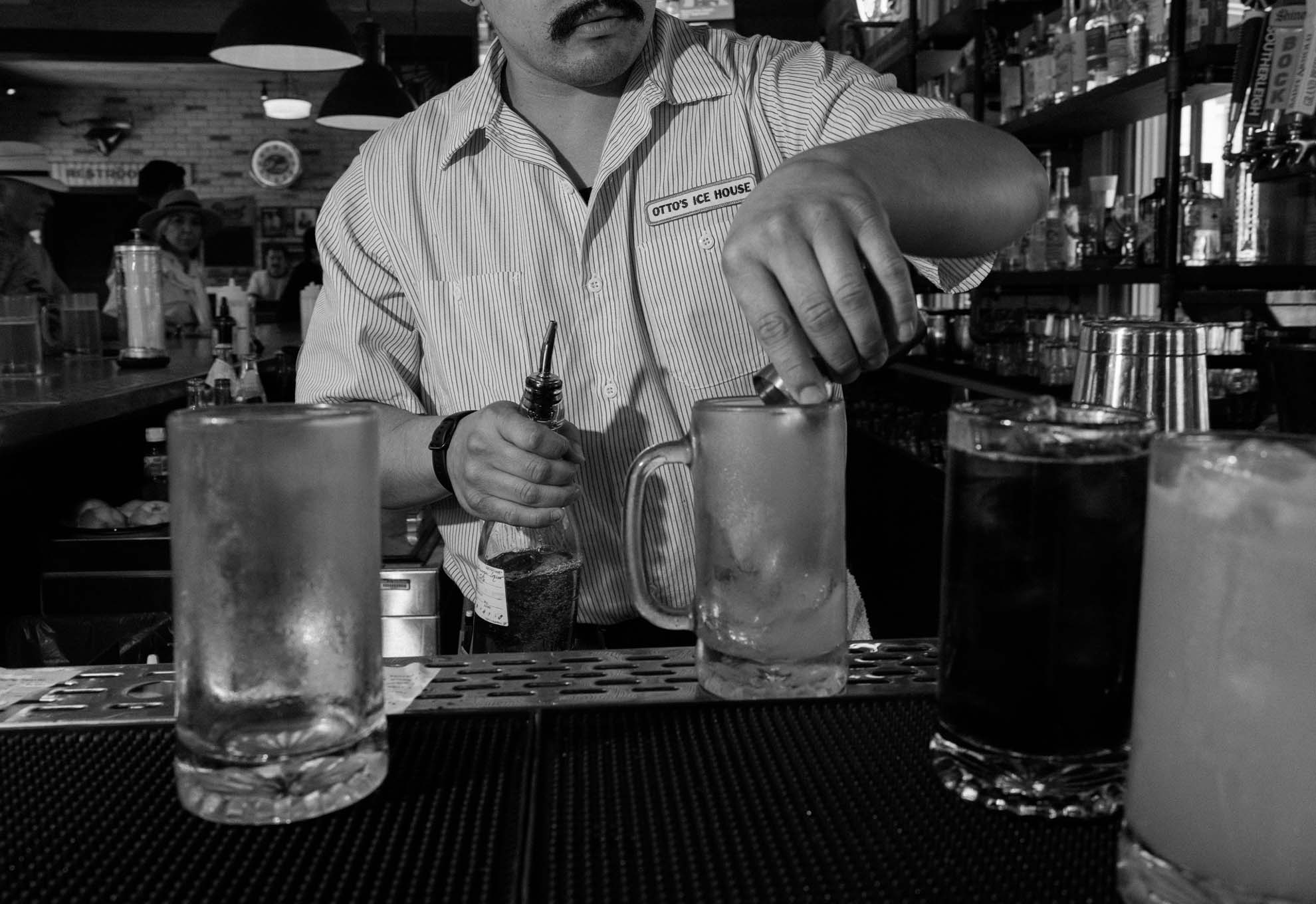

What do you get when you combine shady behavior, Texas history, and a few cold ones? You get my latest venture, Otto’s Ice House, and I’m excited to announce to the world that it’s officially open for business. It’s a riverside watering hole inspired by one of the most unique aspects of Texas’s storied past, and home to more than a few custom cocktails and made-from-scratch bar food of the highest order.

You’d think that would be the end of the article, but there are a few things that may leave some folks scratching their heads—namely, what it is, where it is, and why the hell I named it after a guy named Otto. Well, you’re in luck, because I’m using my digital soapbox to tell you about this fun venture that’s taken my team and me on quite the journey over the past year or so and, hopefully, giving you a few compelling reasons to take a trip to The Pearl in San Antonio. Yep, you heard right. We hit the road and went west for our first concept outside of Houston, which brings me to my first talking point.

Why the Pearl?

My pursuits (and heart and soul) will always be tied to Houston, so it may seem odd that we’re opening a new concept about three hours down the road. It’s hard to answer this question without diving into the history and story behind the place, but I’ll leave it at this for now—The Pearl District is the perfect choice. As an enthusiast for the history behind Texas beer, it’s a pilgrimage of sorts every time I head to the old Pearl brewery and the shops surrounding it.

But, more than The Pearl itself, we had the opportunity to establish a new concept in a prime location along the San Antonio River, and the River Walk itself. With a blank slate, we could fill the place with beer paraphernalia, build it to reflect the exact style we wanted, and flex our creative muscles to create a one-of-a-kind experience for thirsty San Antonians and a few fellow pilgrims. So, I’ll answer your question with another question—why not?

What’s an Ice House?

If you have a good answer for this one, you can email me at howdy@levigoode.com and let me know. While I’m (mostly) joking, the definition of an ice house is pretty damn hard to pin down, so much so that I went to the state’s unofficial beer historian to try and find the answer. I’d recommend reading our conversation, but I’ll do my best to give you the cliff notes here.

Essentially, ice houses were born in the pre-refrigeration days when beer companies were shipping their products across the state (and sometimes country) and needed to keep their kegs cold. The larger beer distributors gave away free ice in an effort to undercut the Texas breweries, which started an “ice war” of sorts and the earliest versions of ice houses began popping up around the state.

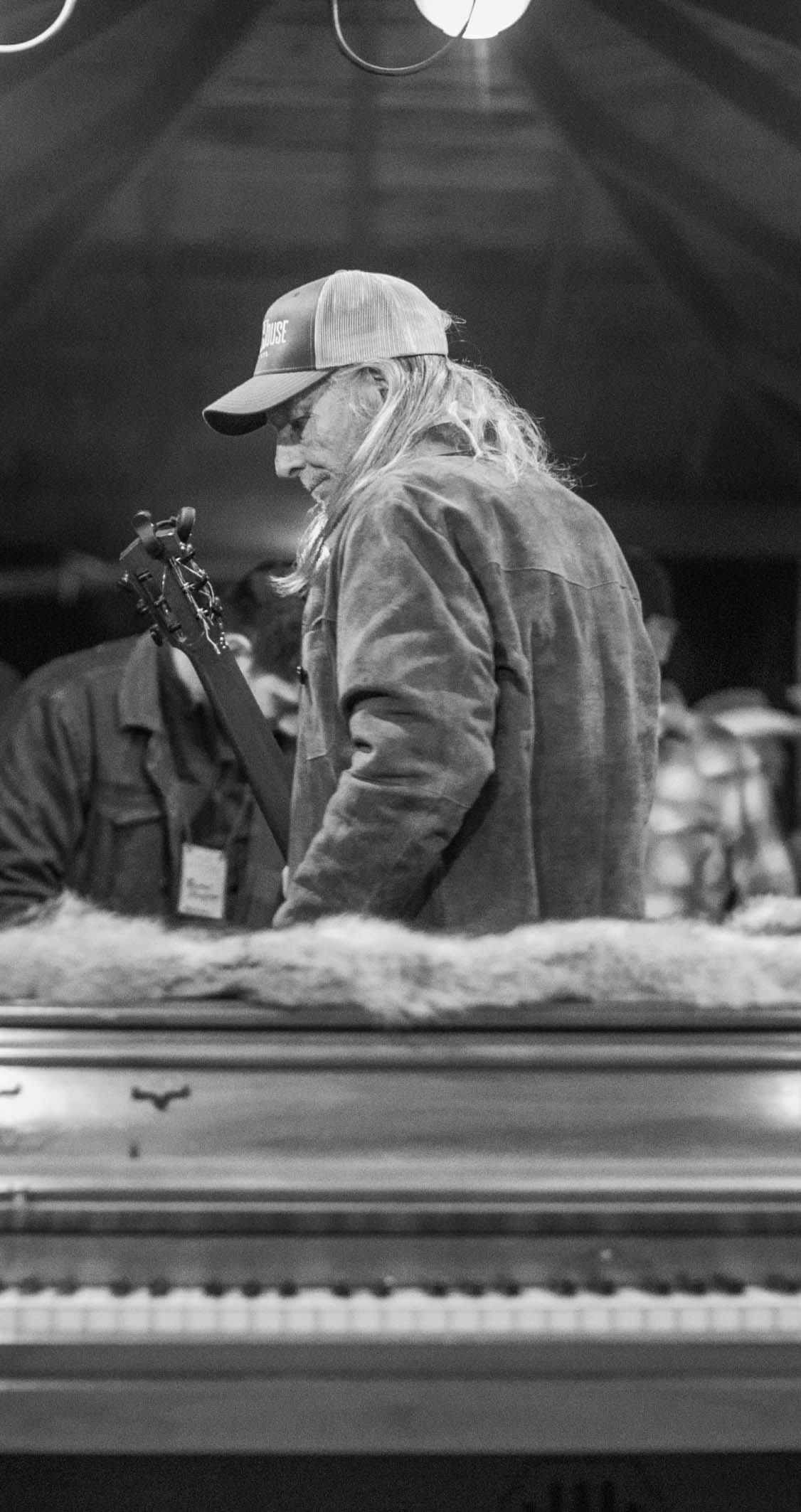

These spots were not bars or restaurants, however, and it took a few decades for the idea to take shape. After Prohibition ended, and when modern refrigeration came into play, the original ice houses faded away and were replaced by social joints more reminiscent of a German beer garden, as opposed to your classic western saloon (which had minimal seating, food, etc.). For a brief period of time in the 1940s–50s, our definition of an ice house materialized. These watering holes were generally indoor/outdoor, regularly had live music, and also served as a convenience store of sorts for locals.

While there are a few ice houses scattered around the state (you can hunt a few down here), most of them have shuttered their doors and turned off the taps. But now I’m happy to say that you can find its spirit intact with Otto’s.

This may not be a clear answer because there really isn’t one. There’s no minimum criteria for being an ice house, but it’s one of those “you know it when you see it” things. More than indoor/outdoor seating, live music, and old-school vibes, an ice house is a feeling—one shaped by nearly 100 years of thirsty Texans looking to come together for a good time.

Otto’s story is much more intriguing when you take into account Emma. And Emma. And Emma.

Who’s Otto?

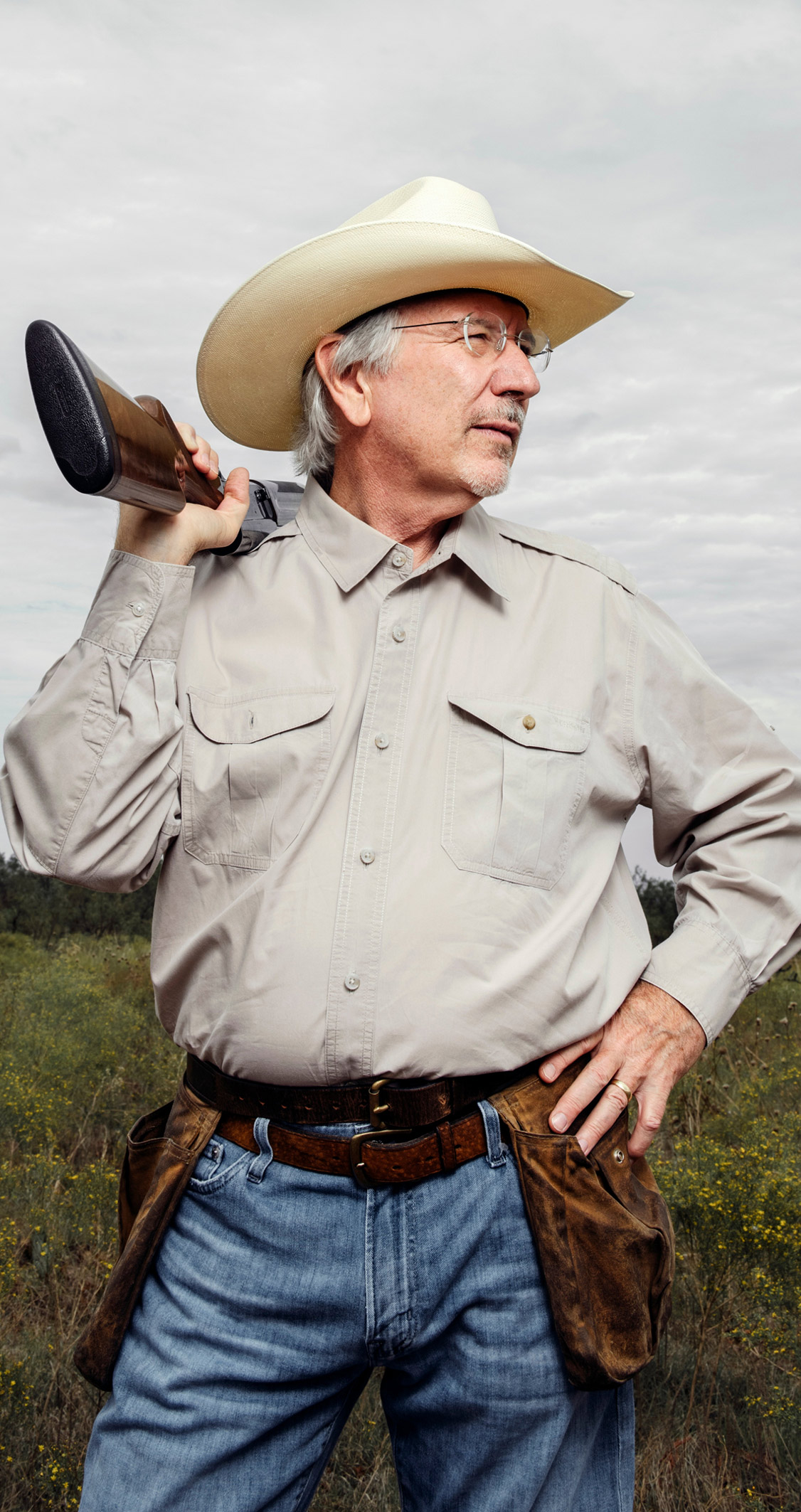

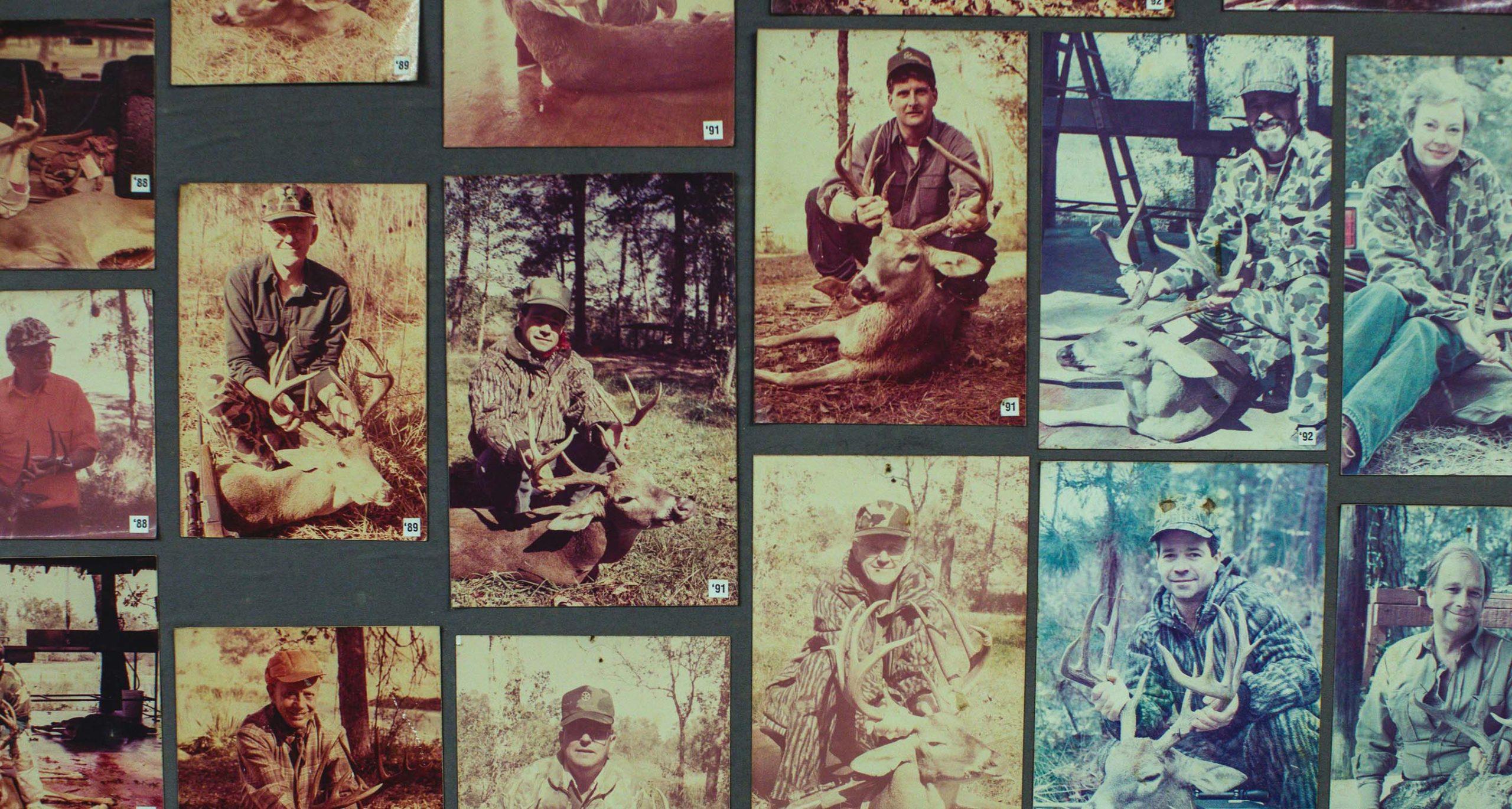

The simple answer is that Otto Koehler was the owner of the Pearl Brewery in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But, we wouldn’t have named our ice house after him if it was that simple. Otto’s story is much more intriguing when you take into account Emma. And Emma. And Emma. Let me explain.

Otto had a soft spot for the ladies, evidently a specific type of lady with the first name Emma. He was married to Emma Koehler, who was a beer baroness and badass in her own right, and would help to keep the Pearl Brewery afloat during some of its toughest chapters. Then, Otto struck up an affair with Emma Dumpke (his wife’s nurse), and eventually struck up another affair with Emma Burgermeister (Emma Dumpke’s roommate).

This love quadrangle goes into full soap opera territory when Emma D. decides to leave Otto for a more suitable suitor, which prompts him to propose to Emma B. while he’s still married to Emma K. Confused yet? Well, Emma B. must have been too, because she was appalled enough to reject him via a fatal gunshot wound in 1914, giving Emma Koehler the reins to the Pearl empire.

So, why didn’t we name the ice house after Emma? Well, Hotel Emma sits across the river, and is a towering monument to a woman who endured despite her husband and hardship. Otto’s Ice House, to us, is a reminder in the form of a slightly shady little watering hole—to be careful of the story you leave behind and, if you’re about to make a poor decision, maybe go grab a beer and think it over first. If Otto had followed that advice, maybe we’d be telling a different story.

Houston will always be home for me and my company, but that doesn’t mean we can’t take the occasional detour to one of Texas’s most iconic communities.

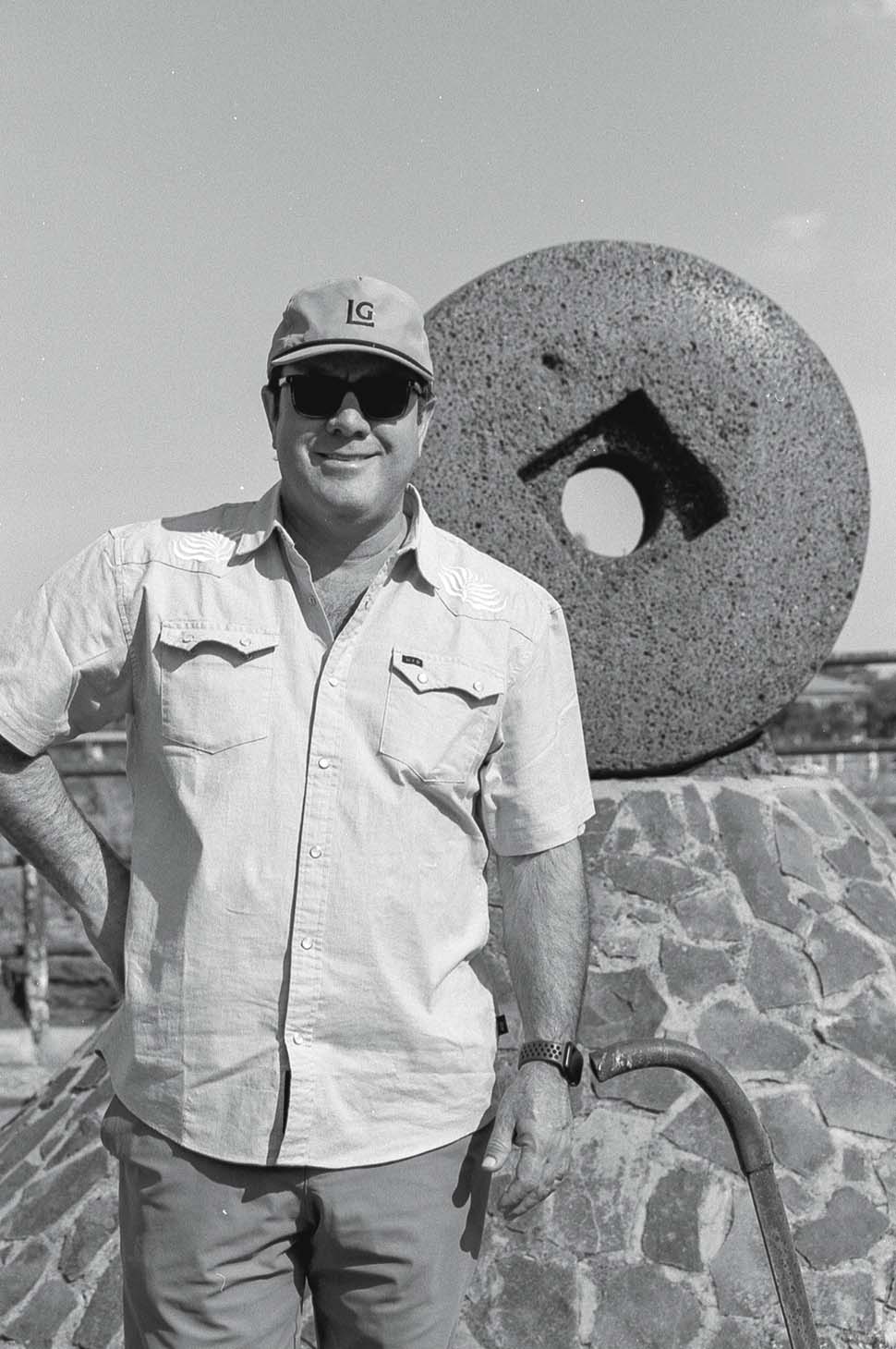

I hope that clears up a few of your outstanding questions. In whatever venture I take on, I lead with my heart and gut first, and Otto’s Ice House just felt right in both regards. Houston will always be home for me and my company, but that doesn’t mean we can’t take the occasional detour to one of Texas’s most iconic communities. Regardless of the city, my goal is that Otto’s will shed light on a slightly dubious history, cultivate some community, and infuse some more fun into an area that’s already bursting with it. If we check those boxes, we may just save Otto’s reputation after all—or at least help it go down a little smoother.

Otto’s is open now, and it has a full menu of cocktails, beers, non-alcoholic drinks, along with homemade small bites and entrées to boot. You can learn more about it, and check out the full menu on our website.

Photography by Brian Kennedy.